Introduction to Continuum Mechanics

“This is wrinkling my brain” – Troy Barnes. I had so much difficulty with this course that I ended up taking it over the course of two semesters. For any previous doubts I had about the field of mechanical engineering lacking in computational challenge, this class more than debunked them. ME 185 is widely regarded as the most theoretical course offered in the mechanical engineering undergraduate catalog, and I can partially confirm that to be true. Of course I haven’t taken all the mechanical engineering courses, but among all the courses I took as an undergrad, this stands out as the most theoretical. Nonetheless, I found this course to be another one of those wonderful, epiphany-inducing courses that causes a paradigm shift in how I view the physical world, reminiscent of an intriguing physics course.

What is Continuum Mechanics?

The word continuum implies smooth, lacking interruption, and infinitely splittable. Unless you’re a robot, our universe is continuous. Space and time are both continuous. Most mechanics classes in undergrad treat bodies and objects as a single, discrete entity. In solid mechanics, solid bodies, while not necessarily seen as rigid structures, are always analyzed as a whole. For example, when analyzing a beam in bending most engineers will only care about the maximum deflection and the max stress. Similarly, even an FEA study designed to calculate the stress throughout the entire beam is still just a discrete approximation and a fitted polynomial. Continuum mechanics treats everything as they truly are: continuous media. For the technical, continuum mechanics is kind of like FEA with an infinite number of nodes. For the layman, continuum mechanics is the study of treating everything like a goo.

What made it so hard?

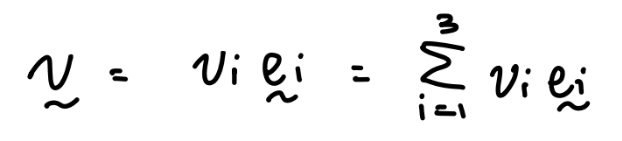

What makes Continuum Mechanics so difficult is the math used to execute it. The easiest math to understand in this course is the matrix algebra. Imagine that. Notation wise, one of the most challenging concepts to wrap my head around was the idea that in an expression, 2 identical variable subscripts implies a summation across said subscripts. Here is a simple example:

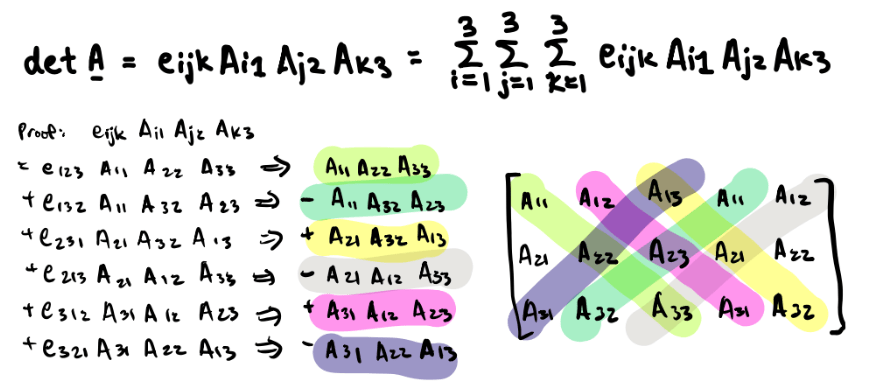

And a more complex one 😖

On another note, the most common operation in any advanced mechanics class is the tensor product. Just like when I first started learning the cross and dot product, the intuition and ease of manipulation around a tensor product takes practice.

What makes it so important?

Continuum mechanics forms the basis of all mechanics! Switch out strains for velocities and suddenly your solid mechanics problem turns into a fluid mechanics problem. Then switch out velocities for temperatures and suddenly you have a thermodynamics problem. I was absolutely shook when the uniform method of problem solving taught by this class turned into the fundamental formulas taught in my solid mechanics, fluid mechanics, and heat transfer courses. In that sense, this course is the father of all classical mechanics. It’s just so mathematically complex that most schools don’t even bother trying to teach it to undergrads.

Food for Thought

Here’s a test of your continuum intuition. Say you have a uniform disk of material with a slice/wedge cut out like Pac-Man. Assume Pac-Man is deformable, incompressible, and the length of his jaw stays constant. If Pac-Man closes his mouth, is he still a circle? Is he an ellipse?