Dynamic Systems and Feedback Control

ME 132 seems rather out of place initially in context with the general ME curriculum. The course felt more like an applied math course than anything else. A distinguishing trait of a mechanical engineering course is the overwhelming sense that the laws of physics are not on our side; that these laws limits of our creativity by creating obstacles we must work around. This course, however, was based on concepts limited only by the extent of our imagination and mathematical abilities. In that respect, this course is abstract in the same way as computer science. Typically, what that means is the course requires mature computational skills and transcends formula application by forcing left-brain critical thinking. Yet, in this respect, the course also feels out of place, leaning towards topics that certainly took some abstract genius to originally discover, but teaching them as if they were the status-quo on how to solve the problems they approach. We were taught exactly which controllers and models were primed to control what kinds of plants in which kinds of environments. The teaching approach was the equivalent of being given a solution to a difficult problem and practicing said solution until it was almost imprinted in our memory. Bear in mind, I take no issue with this approach for this course in particular. The Professor did indeed TRY to show us the intuition behind where these controllers and models come from, giving us a glimpse into a world of control theory that was perhaps more up the alley of an applied math student. As engineers, simply having this broad intuition is enough for such complex topics, and learning the textbook models and how to apply them is sure to be more worth our while.

ME 132 was one of my top enrollment priorities when enrollment for this particular semester opened up, largely due to the fact that I had heard great things about Professor Kameshwar Poolla from upperclassmen. However, I caught Prof. Poolla on an unlucky semester as he had just sustained an injury playing tennis and was stuck teaching from his bed over Zoom as he had multiple back surgeries over the semester. Being the old soul that he is, he had consistent trouble with Zoom and could reliably lecture passionately for about 5-10 minutes without his mic on EVERY lecture. Nonetheless, no hard feelings towards this great Professor. His lecture style (when his mic was on at least) was extremely clear, and he was patient. He took no issue with re-and-re-explaining crucial topics. Lastly, as is an indicator for all great teachers, his lectures were more colloquial than formal and strict. Eventually, his periodic insertion of profanity into his lectures became commonplace enough that we stopped batting an eye, but believe me when I say he lectured as if he didn’t give a damn what we thought of him. I like it when these implied student-teacher filters are removed.

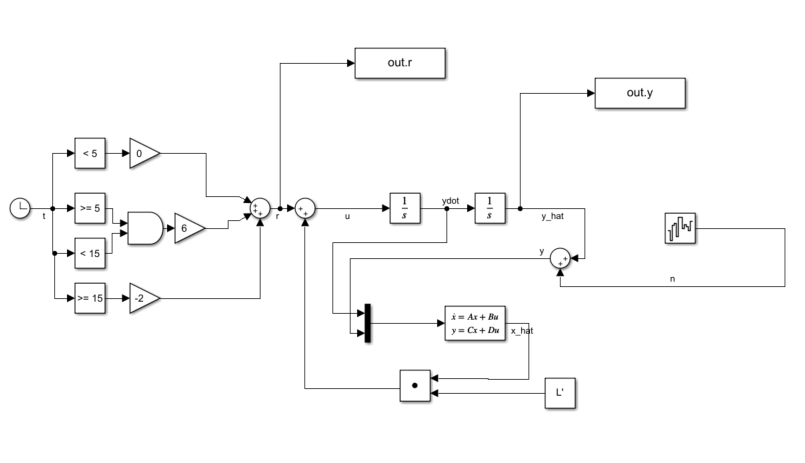

As for the curriculum, this course was a healthy mix between both the theory behind control systems and the practice of using Simulink (a god-tier MATLAB add-on) to create our own models and observe their output. I cannot emphasize how powerful of a tool Simulink is to add to any engineer’s arsenal of skills. Without diving too deep into it, I will summarize Simulink as “making difficult math easy as drag-and-drop”. On the theory side, the course began with a review of differential equations which makes sense as most physical systems that we engineers will be working can be modeled with a differential equation. Next, we were taught the basics of controls (plants, controllers, sensors, input signals, disturbances, noise) and what makes a control model “good” (perfect tracking, robustness, disturbance and noise rejection). The first mathematically tedious topic within this course was application to first and second order systems. Here, fluency in calculus, complex arithmetic, and algebraic quickness became critical. We studied the effects of changing different control model parameters on the output of step-input and sinusoidal-input first and second order systems (transfer functions, DC-gain, poles and zeros, bode plots). Afterwards commenced a deep dive into the more complicated control systems that were more common in industry. This included PI control and extrapolating to linear algebra rather than calculus to handle higher-order systems without needing to do insane integration (state-space analysis). State space analysis was perhaps the most useful takeaway from this course in terms of applicability and gave me heavy deja vu to when I took certain EE courses (see EE16B). Lastly, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the time-consuming and utterly useless labs that recurred through the second half of the semester. We used Lego Mindstorm kits and massive blocks of incomprehensible skeleton code… enough said.

Altogether, ME 132 is a class of endless application. Though fundamentally derivative of EE theory and math, controls can be applied in almost all electro-mechanical systems in the world. How does the segway stand up? How does an airplane know how much to tilt its wings for liftoff and landing? How does a robot arm know where to find the object it wants to pick up? The answers lie in controls. If I weren’t so interested in Aerospace and Astronautics, I would say controls is what I would make a career out of since it is a harmonious combination of my ME and EE backgrounds. Actually, come to think of it, controls WITHIN aerospace and astronautics sounds pretty lit.

Food for Thought

You are working with a robot arm on an assembly line that needs to quickly find the next piece it needs to pick up. As the controls engineer, you have two economic options for controlling the arm. The first option is to use an UNDERDAMPED system where the arm settles in the correct position within 1 second but oscillates before settling (figure 1). The second option is to use an OVERDAMPED system where the arm settles in the correct position in 5 seconds smoothly (figure 2).

If the arm is working in an open space with a high volume output requirement which control scheme would you use? What if the arm is working in a cramped space alongside other arms, but is only used occasionally to pick up defective parts?