Mechanical Behavior of Engineering Materials

ME 108 is considered one of the most critical courses for practical engineering and is the most useful for landing that entry-level mechanical engineering position. As mechanical engineers, we ultimately work with physical systems. Sooner or later, the time will come to choose which materials are considered ideal for the realization of our designs. “Is it better to use 6061 Aluminum or 1045 Steel for the Chassis?”. “Should I be concerned with tensile, compression, or shear failure for this block of concrete?”. “What’ll happen to my plastic container when exposed to long periods of intense sunlight?”. These are the questions that ME 108 seeks to answer.

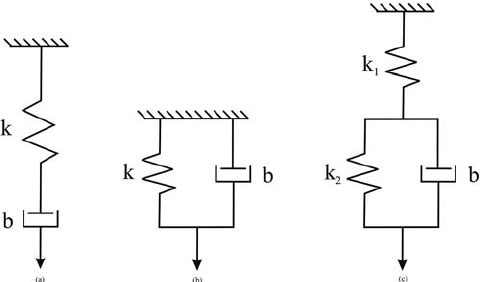

Taught by Professor Grace O’Connell, this course covered topics ranging from the chemistry and crystal structure of materials (and their impact on mechanical properties), to solid mechanics, to the different testing apparatuses and loading modalities that are commonplace in industry. Within this course, our focus was concentrated on two main material types: metals and polymers. We also glazed across ceramics and composites, but certainly not as in-depth as we did the former two. For metals, emphasis was placed on heat treatment methods and stress-strain behavior. For polymers, emphasis was placed on its unique mechanical properties resulting from its chain-like microstructure as well as on its time-dependent, viscoelastic behavior (tendency to behave as a hybrid between a fluid and a solid body).

Specific materials aside, topics such as complex stress analysis built off of material from ME C85 (solid mechanics) and equipped us with the computational skills necessary for finding max stresses and strains possible within any solid body under load. Failure mechanics covered an often-overlooked but incredibly important aspect of engineering regarding how materials fail and predicting when this failure might occur. Lastly, qualitative studies of common existing testing apparatuses (such as the Instron Tensile Tester, Charpy Test, Rockwell Hardness Test, and Dynamic Loading Tester) as well as common loading modalities on test pieces (such as torsion, 3 and 4 point bending, and cantilever testing) provided students with useful peripheral knowledge regarding how theory turns to practice.

One aspect of the course I appreciated was the incorporation of case studies into our curriculum. Every Friday, fully self-aware of the burnout and rapidly deteriorating focus of the majority of her students, Professor O’Connell would opt not to teach any heavy material and focus instead on a historically significant event or product use case that illustrates the application of the concepts we had been learning for the last week. Oftentimes, these case studies were harmless demonstrations of hip implant material selection or heat treatment of car window glass, but occasionally we were presented with harrowing stories of engineering failures costing millions of dollars and lives. The Hyatt Skywalk, the World Trade Center (granted not an engineering failure), and the NASA Columbia shuttle explosion left deep impressions that captivated a tired class and continued to drive home the idea of responsibility and prudence associated with engineering. Though not academic, these case studies will certainly stick with me far longer than the curriculum.

Overall, I cannot say anything terrible or amazing about the course. On the one hand, Professor O’Connell was a great Professor who clearly understood the subject matter, but more importantly understood the students. Unfortunately there to counteract the positives of a great Professor was my disinterest in the subject. I acknowledge its usefulness and will be inevitably applying what I have learned in the future. Nonetheless, the content was sparse and qualitative, two course characteristics which have historically disagreed with me. Too much content was crammed into too little of a timespan with too much emphasis on memorization of facts for this class to make much sense beyond “that is just how things are”. Blind faith in what I am learning as objective fact is risky to me.

Food for Thought

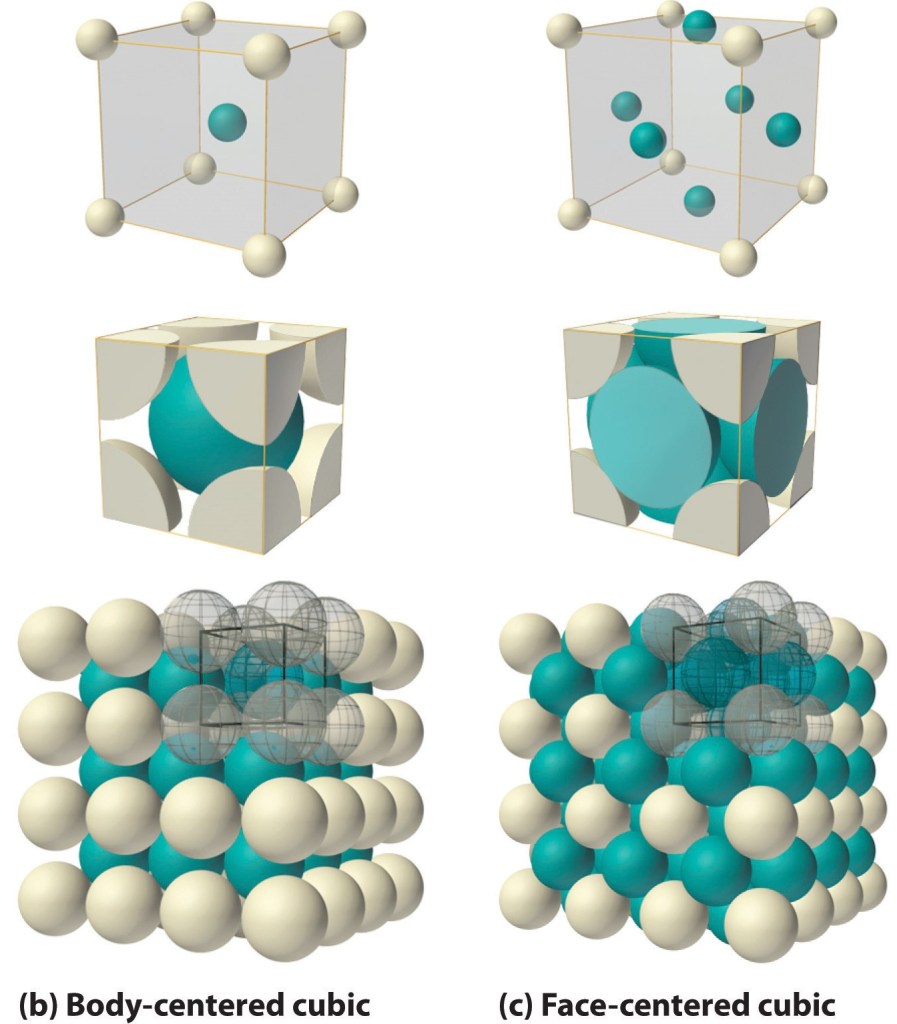

Pictured below are the common unit crystal structures known as body-centered cubic (BCC) and face-centered cubic (FCC). If the atoms that make up the unit cells are the same (or have comparable mass), geometry can be used to determine the density of each unit cell, and hence the material.

Both Austenite and Ferrite are allotropes of iron. Reported yield strengths of the two are 200 MPa and 165 MPa respectively. Without any more information, which of the two is expected to be a BCC crystal structure? Which is expected to be FCC?