Fluid Mechanics

Fluid Mechanics has come down as one of my favorite courses here at Berkeley. My liking for this course is equally credible to the nature of the subject as well as the format, skill, and enthusiasm with which it was taught. My professor for the course was Reza Alam, a professor who I had taken a course with before: E7, Introduction to Programming for Scientists and Engineers (Fall 2019). However, Prof. Alam’s enthusiasm for Fluid Mechanics was readily apparent while his passion for teaching an introductory MATLAB course, not so much. On the other hand, the nature of the subject was heavily computational. For the first time in my academic career, the math in a NON-MATH course proved to be the limiting factor towards my understanding of the subject. Though the first few algebraic lectures were smooth-sailing, soon enough lectures became blackboards speckled with differential equations, line/surface/volume integrals, Curl and Divergence, Laplacians, and the renowned Navier-Stokes Equation. As intimidating as complex math is for students to learn, I can certainly imagine it being more intimidating for a Professor to have to teach. Nonetheless, Prof. Alam approached the course fearless of the math and tackled ALL necessary derivations head-on, leaving little to no room for computational ambiguity. I fully respect and appreciate that. His style also happens to be the teaching style I perform best under.

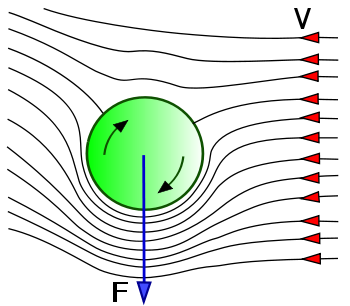

This course began with coverage on viscosity and surface tension, both of which were topics that were not foreign to me, but which I also never deeply studied. Math for these elementary introductory subjects were elementary compared to what was to come, making such topics a nice and soft introduction to the field of fluid mechanics. Next came the Navier-Stokes Equation, the counterpart to Newton’s laws in the realm of liquids. This remarkable, yet unsolved differential equation that seeks to model the dynamics of all fluids is one of the Millennium Problems: 7 problems at the pinnacle of mathematics that, when solved, would likely warrant a Nobel Prize along with a hefty cash prize. Following the derivation and explanation as for the apparent insolvability of the Navier-Stokes Equation, Prof. Alam established a set of assumptions which would carry through for the rest of the course in order to make the problems we encountered more feasible. A whole slew of difficult topics followed, including fluid fields (streamlines, pathlines, and streaklines), flow modeling (using a basis of stream functions such as uniform flow, source/sink flow, and vortices), irrotationality, pipe flows (Couette, Poiseuille), control volume analysis, and changing-mass jet propulsion just to name a few. Only in the final few weeks did the course begin to slowly remove the training wheels of assumptions. These final weeks seemed more practical and covered topics such as dimensional analysis for flow modeling (Buckingham Pi Theorem), CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics), and turbulent flow (Reynold’s number).

With the topics of the course out of the way, I would like to point out an interesting pattern I noticed regarding the homework assignments and especially the exams for this course. Despite lectures topics employing high-level mathematics to establish ideas and derive formulas, assignments did not expect replication of such a rigorous process. It took me a couple homework assignments to realize that I did not need to re-write the integral expression for many problems, and simply plugging into the final formula would have sufficed for credit. Even more surprising was the lack of computational rigor on the exams. In fact, exams focused on conceptual understanding. This seems to break the traditional pattern of computationally-heavy physics-based courses that completely demolish students by creating mathematically tedious problems on exams that take up multiple pages of work. At first , I felt that such conceptually-heavy exams did not accurately assess knowledge of the material and certainly did not reflect the lecture style. However, upon reinspection, I notice that much of conceptual questions encountered on exams required a fundamental understanding of what certain formulas and equations MEAN on an intuitive level. Ultimately, I have come to the conclusion that these exams were almost perfectly crafted to test a level of understanding deeper than 1. Knowing the formulas, 2. Knowing how to use the formulas, or 3. Knowing how to derive the formulas. The exams emphasized knowledge of the physical STORY that formulas try to tell!

To cap this post off, I would like to mention some inspiration for the study of fluids passed on from the Professor, to me, to you. Fluids is a field that, on an absolute scale, is still shrouded in mystery. Due to the nonlinear nature of fluids in the real world, the complexities of finding a perfect model to predict the physical behavior of fluids are too great. On a more philosophical level, we have not yet figured out a way to perfectly control fluids to our liking. Their behavior is not fully within our grasp… unlike most solid bodies. So the next time you see a wave crash onto the beach, take a minute to appreciate the fact that no single wave that has crashed anywhere at anytime in the past or future will be the same as the one you just witnessed. When you hear the rumble of the break, appreciate that no single sound signature ever created will compress the air around you in the same way as the one you just heard. Wonder at the untamed, unpredictable, and inexplicable nature of these spectacular states of matter.

Food for Thought

A glass of milk rests on a scale. You dunk your Oreo into the milk without touching the bottom of the glass. Does the scale reading go up, down, or stay the same?