Thermodynamics

ME 40, though simply called “Thermodynamics”, should more appropriately be called “Graded Table Reading”. Taught by “Professor” David Rich, this course applied the thermodynamics concepts learned in a physics class to real devices and systems. Topics covered included different engine cycles, heat pumps, refrigerators, entropy, and humidity. I will not sugarcoat my distaste for this course. This was due to a variety of reasons.

First, this class represented the greatest pet peeve I have towards engineers: we simplify too much and stop asking questions about our simplifications afterwards. It is the reason why I admire pure fields such as Math, Physics, and Chemistry: they are unwilling to leave anything unanswered and ambiguous. I understand that often, simplifying and blackboxing certain concepts and processes are the most practical way to utilize previously discovered knowledge and come up with an organized way to arrange a workflow. These are all desirable when it comes to engineering, and simplification is a necessary evil I have learned to accept to a certain degree in my studies. This course takes the simplification a bit too far. Too often, our problems devolved into being fed an equation and simply looking through and interpolating endless pages of tabulated values printed at dictionary-font for the correct value to plug in. It was so dry, yet so time consuming. At the end of problem sets, I had spent 6 hours looking through tables to find a value associated with the specific heat at constant temperature of this supercritical fluid, yet not understanding the significance of this value and how it comes into play in the empirical formula. My true understanding of thermodynamics made zero progress in this course. My high school teachers did it better.

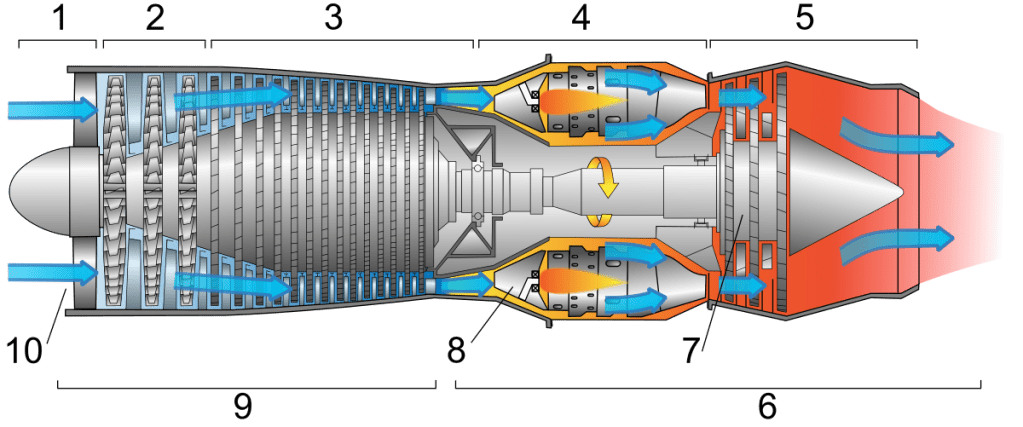

On top of mind-numbing table searching and formulaic plug-and-chug, another aspect of the curriculum I could not stand was the oversimplification of complex thermodynamic devices that represented historical feats of engineering. We turned jet turbines, dehumidifiers, and pumps into little boxes and triangles on our page and learned only the set of rules regarding their input and output thermodynamic states. We were not taught why certain states changed or stayed the same. We were not led to question the mechanics of a jet engine, only to modularize it and set it aside in our heads. I understand that this course may be taking a top-down approach to learning these concepts by introducing the high-level operational understanding first before trying to teach the intricacies of each device (which likely comes in a future course). Regardless, it does not change the fact that this course left too many questions unanswered and essentially became a course on memorization.

This leads me into my last grievance: Professor Rich was not great. He spent a large majority of lecture telling stories of old projects he had as an engineering consultant. In fact, he is still an engineering consultant on paper, and not a Professor. How he is able/qualified to come teach Berkeley Engineering is beyond me. He often makes mistakes during lecture, which a STUDENT typically points out about 20 minutes after the fact. At that point, he may as well have not taught the last 20 minutes than teach it based on a wrong assumption. Overall, I think this professor has spent too much time emphasizing the practical aspects of his work during his time in industry that he has forgotten that a large part of a college education involves cultivating curiosity. I hope all the other Mechanical Engineers out there had/have a better experience learning Thermodynamics.

Food for Thought

Entropy (intuitively described as the “measure of disorder in a system”) is actually rooted heavily in probability theory. The building blocks of entropy are called “microstates”, which are a unique configuration of particles that may possibly exist within a system. Consider the simple model shown below with 4 particles and 2 bins with the shown microstates.

Each row corresponds to microstates with comparable entropy, which is related to the number of particles in each bin (the identity of the particle does not matter for entropic purposes and are only color-coded for distinguishing purposes).

- Which row represents the state with the highest entropy / the state which the system will naturally tend towards?

- In a system with n particles and N bins, how many total possible microstates exist?