Macroeconomic Analysis for Business Decisions

UGBA 101B, taught by Professor David Levine, was a course that reconciled macroeconomic concepts from traditional economic curriculum with business decision-making. At its core, 101B is an economics course more than anything else. The course covered both qualitative and quantitative macroeconomic topics which were applied on a 3-part deliverable case study which had students identify and analyze the macroeconomic differences between two third-world countries and their implications on a hypothetical company. Otherwise, the homework sets and exams were mostly concerned with pure macroeconomic concepts, making this course much more of an in-depth dive into macro concepts introduced in Econ 1.

I will quickly gloss over the curriculum first. As already mentioned, this class covered many quantitative economic topics which I had previously learned in other courses dating all the way back to senior year of high school. Such topics included inflation, unemployment, exchange rates, etc. However, this is not to say I did not learn anything from repetition. Repetition breeds mastery through reinforcement.

Despite the straightforwardness of simply modeling economic systems using formulas, qualitative analysis dominates the game of economics. The fact that 101B strayed from the “numbers never lie” mindset that many intro econ courses cling dearly onto was a refreshing new take on economics. The insistence of intro econ classes to trust grossly oversimplified number-based models had always irked me. As a numbers-person, I was good at it, but it simply did not feel right. 101B introduced topics such as infrastructure, geography, government stability, and education among a host of factors that can greatly influence a nation’s economy yet remain invisible to the GDP = C + I + G + X equation. In lecture, problem sets, and even exams, we were often encouraged to answer “it depends”, so long as we had solid justification to support our claim. Best of all, Professor Levine never let a numerical value be an end-all be-all to any explanation. We were always asked to tell the “story” behind the number.

Another significant part of the course was the case study. In our case study, we were given the full current situation of a hypothetical company that produces car batteries and competes directly with Tesla (Musk’s presence is literally everywhere…). Considering the full picture of the company, each group was asked to consider two vastly different countries to build a new terafactory in. Our group chose to analyze the Shandong province of China and Mexico. Each country was researched and broken down by factors such as GDP, labor force education, and wage volatility among many others. I will forego the details of our findings and instead express how much I appreciate 101B for teaching me to be mindful of the real world. Professor Levine heavily weighed current event knowledge in his exams and case studies. I all too often forget to tie what I learn back to the world which is immensely important especially for economics.

Overall, 101B renewed my interest in the study of economics. To be fair, I had always subconsciously known that economics could not be as bland and simple as the intro courses made them out to be. After all, there’s a whole Nobel Prize category dedicated to the field of study. Therefore, if anything, 101B simply confirmed that economics is a more complex and beautiful subject than finding where the S and D curves cross. Thank you Professor Levine for causing a paradigm shift in my understanding of economics as well as for forcing me to read the news and care about Japan’s interest rates :).

Food For Thought

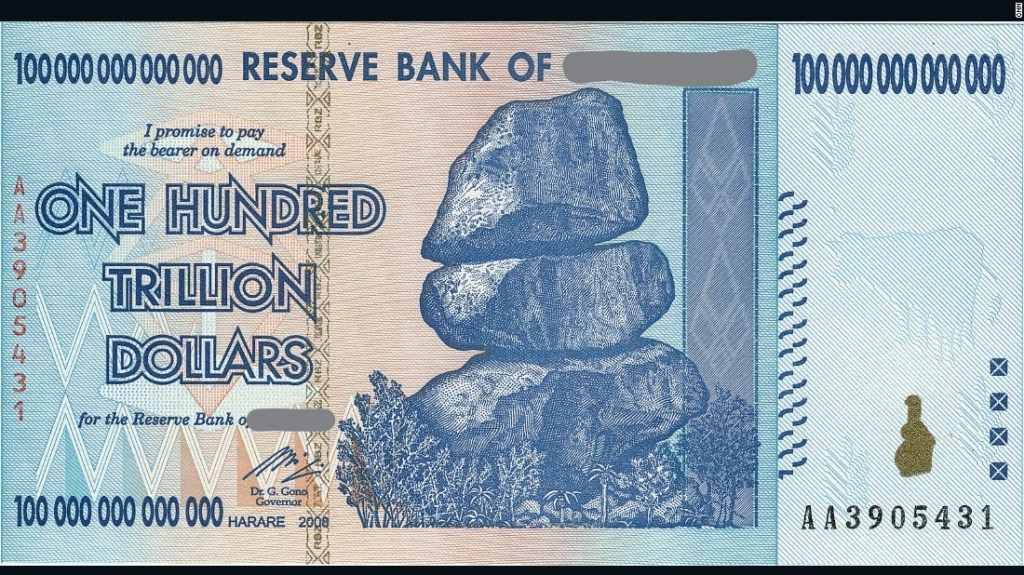

There is a country where a trillion dollar bill exists, bread costs $35 million in local currency, and most everyone is a billionaire, yet most everyone is hungry. Which country is this and what led to this fate?