Engineering Mechanics II

Engineering Mechanics II is a course that seems to re-teach many of the concepts introduced in an elementary physics course using more sophisticated mathematical concepts. This included treating all appropriate variables as the vectors they really are rather than the scalar form they may be simplified to as well as respecting all rules of single and multi-variate calculus and vector operations. Yet, perhaps the most prominent example of utilizing higher level math in this course was the introduction of a corotational basis of coordinate vectors for rotating rigid bodies, and the use of the tensor matrix: a mapping between basis vectors. Taught by Prof. James Casey, this course ensures that all mechanical engineers have a cemented understanding of the most fundamental, well, engineering mechanics.

Kinematics

Characteristic of a first year physics course, this course also begins with kinematics (the study of how objects move). Linear, rotational, and combined motion was the focus of the first few weeks of the course. Some of the vector bases for motion beside the standard i, j, k basis introduced were the cylindrical basis, corotational basis, and Frenet-Serret basis. Many of the problems in the kinematics section of the course involved solving problems in multiple bases and being able to transform solutions from one basis to another. Calculus was used to derive the differential equations used to solve problems. The beauty of these equations lay in the fact that they were general equations and applicable to any basis of vectors! To transform between bases, linear algebra was involved. This was especially interesting to me as this was the first time I had used linear algebra in a physics course. Eventually, our intuition grew mature enough to allow us to determine the basis for which solving a specific problem would require the least tedious calculation.

Dynamics

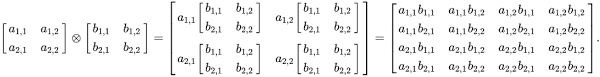

The natural follow up to kinematics is dynamics (the study of why objects move). Here, we were reintroduced to Newton’s laws which were re-labeled as Euler’s laws instead (this caused quite a bit of confusion initially). This was also the section of the course where forces, torques, moments, masses, inertia, and energy came back into play. Additionally, the second half of the course took a closer look at the linear algebra used in the kinematics section of the course. Eigen-decomposition mathematically demonstrated how to find the basis of vectors best suited for solving a particular problem. Eigenvectors became the unique corotational basis used to solve problems. In congruence with the linear algebra, tensor products (cutely shortened to ‘bun’) were introduced. Inertia tensors came to replace the simple concept of single, scalar-valued inertia. The problems in this section of the course became increasingly difficult as more concepts, relationships, and mathematical tools were married together to come to a solution.

Overall, ME 104 did not teach me much in terms of new knowledge with the exception of tensor products and matrices. Nonetheless, I realize the importance of this course in context of applicability. The problems I encountered in this class were not simplified in order to be “nice” to students as many physics courses do. Each concept taught originated from established laws and subsequent concepts were derived mathematically. As engineers it is unreasonable to expect any real-world problems to be “nice”. This course reinforces the importance of tackling problems from the ground up without making any unsafe assumptions that are all too tempting to make for the sake of making the problem “nice”. Incorrect assumptions and attempted shortcuts are ruthlessly punished by an incorrect answer after an hour of slogging through calculations. The attention to detail and fundamental problem-solving style mandated by this course is not to go unappreciated.

Food For Thought

A dot (inner) product between two n-dimensional vectors produces a ______, and a tensor (outer) product between two n-dimensional vectors produces an _ x _ ______.

Knowing this, what does a tensor product between two n x n dimensional matrices produce?

Bonus: Why is it incorrect to say “a cross product between two n-dimensional vectors produces another n-dimensional vector”?