Introduction:

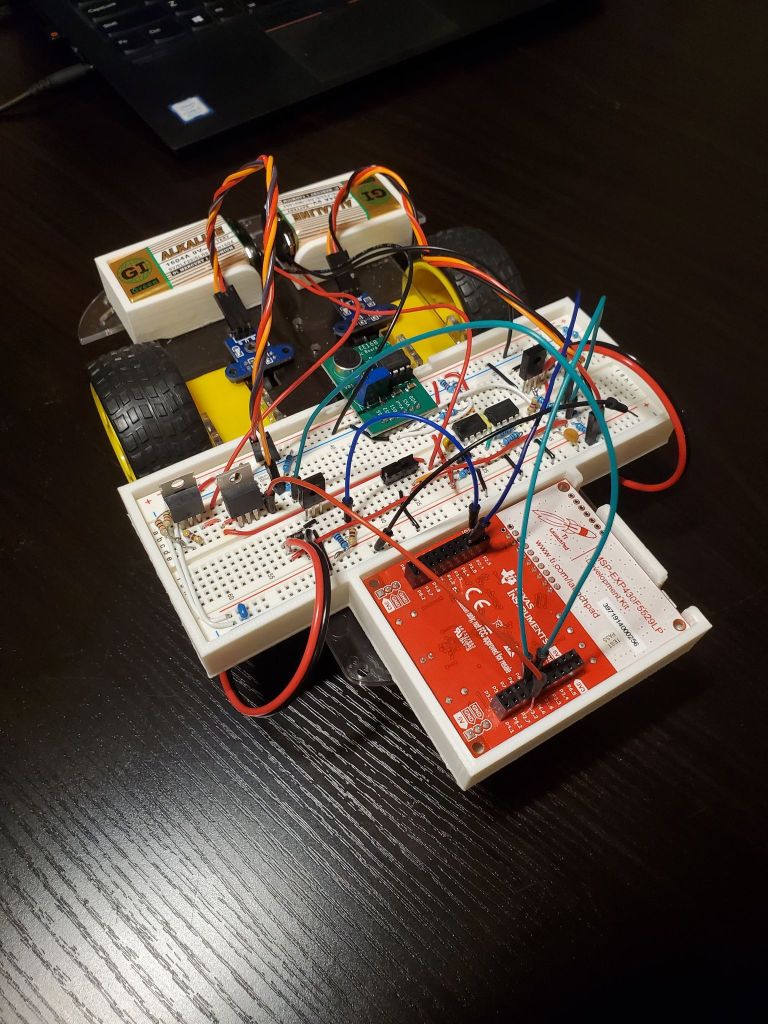

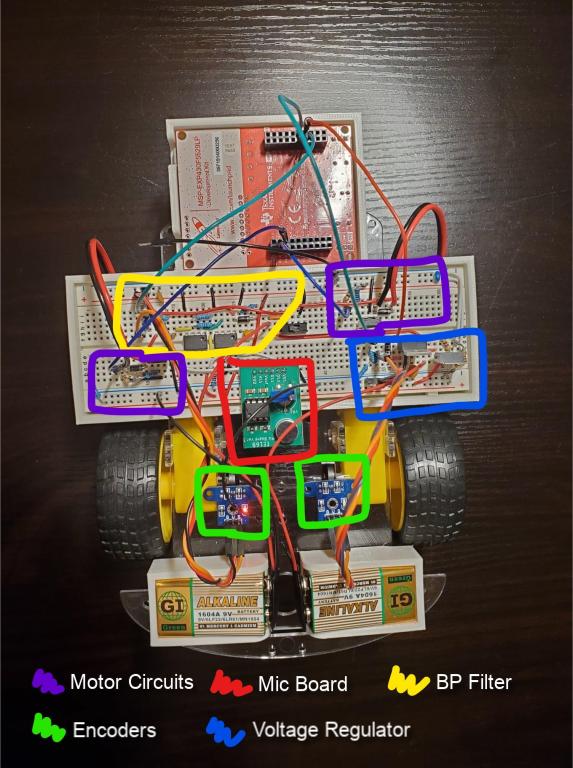

This car is a voice-controlled car that takes in 4 commands. The command “GO” makes the car move forward for about three seconds. “GO GO” makes the car move forward for about five seconds. “Leeeeft” makes the car go left. “Turn Right Mon” makes the car go right. Why the odd commands? Stay tuned to find out. This entire project is a simple concept made difficult due to the how prehistoric and low-level all the equipment was! The motors were cheap motors without a servo port and inconsistent levels of rotational speed. The circuitry components were all basic op amps, resistors, capacitors, and a single mic board which could by calibrated to convert auditory cues to changes in voltage. The point of this project was to use simple circuit components to create a more complex and useful system as well as to process the information outputted by this system using Launchpad code.

Front-End Circuitry and Hardware:

The Front end of this voice-controlled car mainly involves frequency filter circuits and voltage amplification using op amps. High and low pass filters are cascaded to form a bandpass filter that passes voltage signals of a certain frequency. These voltage signals were generated by a mic board that requires precise calibration. Thus, my bandpass filter could “listen” for sounds within the vocal frequency range of the human voice. After amplifying signals within the desired frequency range using op amps, vocal cues have successfully been converted to electrical signals. My car can officially listen to me.

Controls:

The controls aspect of this project did not involve the mic or vocal recognition in any way yet was a continuation of front-end circuitry. By controls, I simply mean making the car go straight and turn right / left at a reasonable radius of curvature without overshooting. Otherwise basic tasks for a servo motor, this was made ever more difficult by crap motors. First of all, I had to install my own encoders and photogates to read the rotational speed of these motors. After all the necessary circuits for motor control and tick reading were implemented on the breadboard, the real work began. First, I ran simple calibration tests that determined the base rotational speed of each motor given a range of voltages. Next, in the Launchpad, I implemented a closed-loop control scheme. In general, the scheme involves using the difference in wheel rotational speeds and multiplying this difference by a k-factor to determine the necessary adjustments in speed of each wheel upon the next discrete timestamp. To go straight, the car would adjust wheel rotational speeds with a target difference of 0 ticks/second. To turn right or left by a certain radius, the target difference in wheel speed was adjusted to a nonzero value based on some basic kinematic equations. The car has learned to walk.

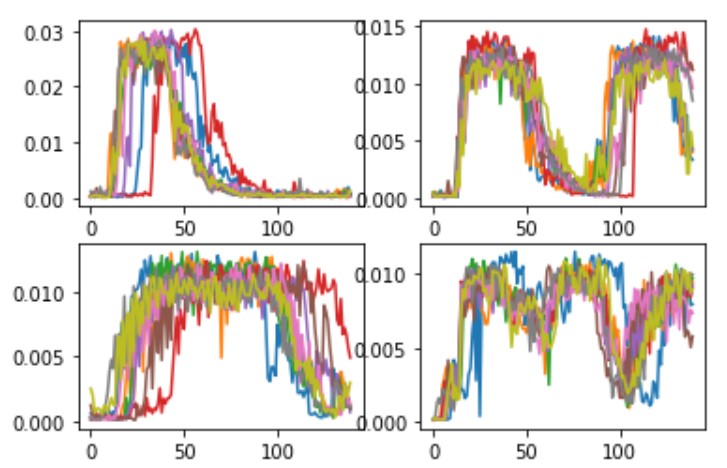

Signal Classification (SVD/PCA):

Lastly, yet most importantly, the car needs to understand my commands. The car is programmed to listen over a two second interval. Within those two seconds I need to say something that is easy for the vehicle to identify. I chose to go with the aforementioned commands because of their syllable count and length. Each one created a different voltage signature which would be easy for my car to reliably classify. As for the actual classification algorithm, I will no go deep into the linear algebra behind singular value decomposition (SVD) and principal component analysis (PCA). In simplest terms, the car takes in all the training vocal cues I give it and sums it all up into two nice parameters (two “principal components”). Whenever I speak at the car the car takes my words and maps it onto both principal components creating a coordinate (x, y). Then classification is simply a matter of finding the preprogrammed command closest in distance to the speech. Finally, my car is able to think.