Build Your Own World is a Java-based game that uses data structures, algorithms, and the StdDraw library. I, along with my project partner Dayne, created a Player vs Player game where players compete against each other to collect as many flowers as possible. Flowers are randomly strewn across the world. The world consists of a system of rectangular rooms and hallways. Hallways connect rooms together. The players have the option to either play with the lights on or off, in which case only a small subset of blocks within the player’s field of view are visible. Additionally, players can choose to save and quit their game to continue later. The next time the player opens the game, they can either choose to load the last saved world or create a new world by inputting an integer seed. Player one controls their avatar with WASD while player two uses IJKL. In case of confusion, the user can determine the type of block they see by hovering their mouse over the block which displays the type of block the mouse is currently over.

Although the game gives off retro/80’s vibes, it was still quite a challenge for a relatively unexperienced programmer such as myself. The entire project took a cumulative 30 hours split between both my project partner and myself. Throughout the coding process, I faced many thought-provoking obstacles that gave me a newfound appreciation for the difficult work of game designers. Here I will outline the problems confronted throughout our project and the solution we implemented to solve them.

Room Generation:

Room Generation was the first task that we had to tackle. How can we generate randomly dimensioned rectangular rooms from a blank black world that are evenly spaced throughout? For starters, it must be mentioned that “randomness” in a lot of computer programs are in fact still systematic. Randomness is ultimately determined by the integer “seed” you feed to the program. There are simply so many seeds that the probability of the same world being generated is practically negligible. In order to generate random rooms, with random placement, and random dimensions (lots of randomness going on here), we needed to use a seed-based random number generator that would generate the respective values.

For starters, we needed to determine the number of rooms to create. This was achieved by using random selector over a uniform distribution from a range of 20 to 40 rooms. Throughout most of the project, we used selectors over uniform distributions with a min and max bound instead of a normal distribution. This was done in order to mitigate the small but problematic probability of generating an underwhelming single-digit number of rooms or even an erroneous negative number of rooms. The next problem was where to generate the rooms. We decided to place rooms based on reference point. All this means is that each room would start as a point and will be told to “grow” in a certain direction until it is told to stop by an external indicator. To ensure even room distribution, we split the window into quadrants, with the dead center of the window acting as the origin. Then, we generated random points within each quadrant until the number of points matched the number of rooms from determined from the first step. Points were as evenly distributed throughout the quadrants as possible. Using the quadrant partitioning method ensured a baseline level of acceptable room density. We did not want to have a generated world where the all the rooms were generated on the left side of the world for example.

The last step was room growth. We iterated over each room repetitively, growing each by one unit in a random acceptable direction (NSEW). An example of an unacceptable expansion is if a room decides to grow North, but there already exists a room there or the room has hit the edge of the world. Rooms would stop expanding under either of two conditions. If the room is unable to expand in any one direction, then expansion stops. However, upon each iteration, the room also had a 25% chance of stopping expansion. This 25% probability only kicked in after at least 5 room expansions. This was implemented to ensure that rooms that were not unreasonably small (1 unit by 1 unit). Additionally, the 25% rule was implemented to ensure that rooms did not expand until it became impossible to, thus creating very little space for hallways or just empty space.

Hallway Generation:

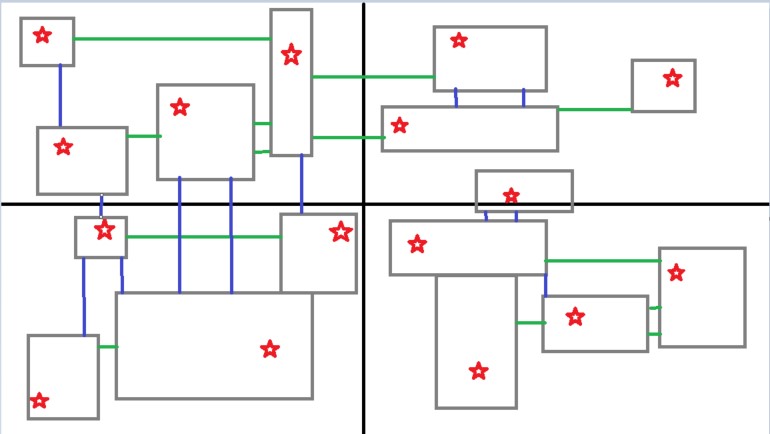

Once rooms have been generated, the next task is to determine how to generate hallways. Hallways can run either vertical or horizontal and must start and end in a room. Some hallways may and should intersect, creating a cross. First, we generated horizontal hallways. All horizontal hallways need to span from one room’s East wall to another’s West wall. The first task was once again to determine how many horizontal hallways we wanted. This was usually a function of how many rooms were generated throughout the world. After determining horizontal hallway count, we randomly chose a room and in each room we randomly chose a unit along the East wall. At each unit, we would determine whether a horizontal hall was valid to start there. To be valid, the unit must have another room’s west wall along the same line of latitude ready to receive the end of the hall. Additionally, the walls on either side of the hypothetical hall cannot overlap with any existing features and must be blank space. Once a unit along an east wall was deemed valid, a wall would be generated from said unit to the west wall of another room. The entire process repeats (now with the existing hall) until the number of horizontal halls reaches the target count, or no other horizontal halls can be generated.

Horizontal Hall Generation (Green)

Vertical Hall Generation (Blue)

The process of generating vertical halls was theoretically similar to generating horizontal halls, except with north and south walls of rooms. However, there was one key issue that our generator needed to work around. Since the horizontal halls would already exist when the vertical hall generator began running, the generator needed a way to not confuse horizontal halls with rooms. If the generator thought a horizontal hallway was a horizontal room, it would stop generating once it hit the hallway, thus violating the requirement for hallways to start and end in a room. This was fixed using a simple but un-robust manner. We generated the horizontal halls with block types that differed from the rooms and their walls. This way, the rooms and hallways would be distinguishable to our code in the middle of the hall generation process. Only after all halls finished generating would the block types be changed back to match the types of the rooms and walls.

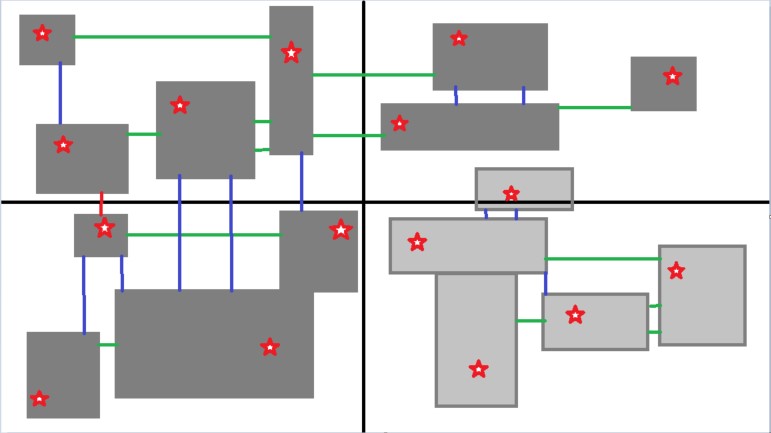

The last obstacle to tackle was the trickiest one. Rooms and hallways needed to be connected! It would reflect poorly on the intelligence of us game creators if an inaccessible room were generated and the room contained a flower to be picked. The solution required a simple connectivity algorithm which would start at a random block within either a hallway or a room. The algorithm would iterate across all the blocks connected to the starting block and count + mark them. If the count matches the cumulative sizes of all rooms and hallways combined, it is clear that the entire world is connected. If not, we observed the unmarked blocks which comprised of the unconnected system of rooms and hallways. We then generated an additional hallway from an unmarked block to a marked block, thus connecting the two systems. The process resets (all marked blocks become unmarked) and repeats until the connectivity algorithm determined the entire world was connected.

Light Gray subsection is disconnected from larger network

Random additional hallway deemed necessary for connectivity

Loading Saved Worlds:

The remaining obstacles we tackled differ from world and hallway generation in that they were much more logistical than technical. These problems did not require much logic and thought and instead emphasized our ability to store data and use existing libraries within our code.

In order to load a saved world, we needed to store all of the world data somewhere. However, once the game ends and the program terminates, the existing world is erased and the runtime memory of the program is cleared. As a result, we decided to simply store the data locally in a text file. Once a game is saved and quit, a text file is either written (if one does not exist yet) or is rewritten with the most recent world data. World data includes the seed with which the random world was generated with, the coordinates of all flowers, the coordinates of both players, and the score of both players. When the player requests to load a world, our program simply reads the text file and generates the entire world again with the same seed. The world will be identical to the previous world. The last step is simply to place all flowers and players back to their last spot, and update the scoreboard from the default 0-0 to the last score.

UI:

You may be wondering how we turned all of these hypothetical ideas into a viewable, playable window on your screen. To generate the UI, both for the menu navigation as well as the world, we spent some time familiarizing ourselves with the StdDraw class from the Princeton CS library. This class came with all the functionality necessary for our game: displaying text and blocks, prompting user input, sensing mouse location, and most importantly double buffering. The first three are fairly self-explanatory and it is obvious where we used such functionality in our game. Double buffering was the most difficult function to learn but was also the most important. Because our world was dynamic (players are constantly moving around and picking up flowers), we were generating a new image on the screen every time a visual change to the world needed to be made. Unfortunately, this meant that the UI was constantly flickering between a blank screen and the world, making for an uncomfortable gaming experience. Double buffering allowed a grace period between the clearing of the old UI and the displaying of the new UI, this making gameplay much smoother.

Recap:

Overall, there were a lot of smaller problems that this project presented that I did not mention above. Many of these were too minute to mention without making this post needlessly long. As well, some of the game features such as player movement, flower picking, and score keeping were handled by my trusty project partner. Though I know the general gist of what he did, I am not confident in my ability to explain. Nonetheless, this brings me to my last point. This project offered not only an opportunity to sharpen my coding skills, but also taught the both of us to work with and value a project partner. Collaboration is all too present in the world of engineering, whether it is software or hardware. Though it is dangerously easy to get lost in one’s own thoughts and ideas, especially in a CS project, I should always remember to stay open minded and listen to the constructive input of others. That is why to close, I will give a shoutout to Dayne, who helped loads with both the ideation and execution of our project. Strong work!