Introduction to Economics

I apologize in advance for the negative feelings I have about this course. This course was nothing special. Do not get me wrong, the course was decently well taught given how much it needed to cover in such a short time as well as the circumstances of remote learning. There simply was nothing that stood out about this course for me. Econ 1 was a dry but necessary introduction to a subject that requires much more than one semester to unravel. In fact, the curriculum was almost a cookie-cutter copy of the economics course which I took in high school. Perhaps I learned the subject more effectively then.

As a disclaimer, this course is not the famously excellent economics course taught by the renowned Romer couple of the Berkeley faculty. I made a mistake not enrolling with their class. Though the subject matter may be similar, my professor, Professor Tang, was less experienced in teaching economics than the Romers (she was new to Berkeley at the time). Her lectures seemed slightly rushed and she always sounded anxious about not being able to cover all the necessary topics within the hour. Her style of teaching was also textbook. Bulleted slides would outline main points and topics that should be interpreted with subjectivity became an unquestionable fact in the scope of the course. The many economic models introduced simplified the subject to a point of triviality. In addition, her exams, which were a series of quizzes throughout the semester, were unexpectedly easy. They were certainly easier than the tests I received in my high school economics class. Easy exams are both a blessing and a curse. The blessing is obvious: there is less stress and time-commitment on the student’s part. However, the curse is subtle and frankly requires a certain degree of academic maturity to be disappointed over. The easier the exam, the less motivated you are to study, listen to lecture, and just generally learn the material. When such is the case, a course almost becomes pointless. The value from the course dissolves down to just a couple units on a graduation track and a GPA boost. Unfortunately, this is what Econ 1 became for me.

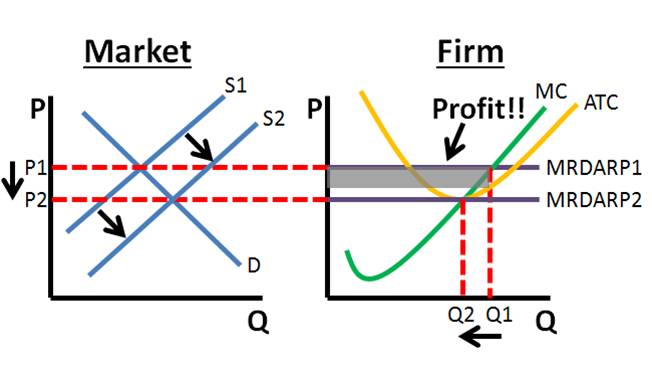

As for the curriculum, I will not dive deep into specifics. The curriculum barely deviates from the standard intro to economics course, and there simply was not enough time to explore any one topic in depth. In fact, performance in this particular course’s curriculum primarily boiled down to an ability to read graphs and rationalize certain economic factors (or memorize them if they really do not make sense). I am no economist, but I am positive this is not what economics ought to be about.

Overall, I want to emphasize that my opinion on the class is heavily biased by the fact that this course was essentially a repeat of something I had learned recently enough that much of the curriculum was still in my mental archives. For a student new to economics, this course provides a solid foundation to economic topics, and may very well prove interesting. I, however, cannot say the same about the course setup. It is frustrating when a topic which is rooted in psychology and decision making boils down to a strict science with laws and models. Nonetheless, I fear there is no alternative for such broad foundational courses that need to cater to hundreds of students every semester.

Food For Thought

Context: The famous Prisoner’s Dilemma is a model for decision analysis between two parties that face different consequences for the same decision. However, the Infinite Prisoner’s Dilemma is a slightly altered version where instead of the decision being a one-time-deal, the decision is recurring infinitely.

The Setup:

Lord Farquaad is hunting fairy tale creatures again. Gingy and Gingette run into Farquaad every day when walking from the Muffin Man’s bakery to Shrek’s swamp. Each time they run into Farquaad, they are each given a decision outlined in the table below.

| Gingy turns Gingette in | Gingy spares Gingette | |

| Gingette turns Gingy in | Farquaad takes 3 bites of each | Farquaad eats 4 bites of Gingy and Gingette walks away |

| Gingette spares Gingy | Farquaad eats 4 bites of Gingette and Gingy walks away | Farquaad takes 1 bite of each |

The two cannot read each other’s decision. At the end of each day, upon returning to the Muffin Man’s bakery, the Muffin Man patches up all of their missing bites and returns them to normal.

The Catch:

- If this were not a recurring situation, the Nash Equilibrium is that both turn each other in. However, once Gingy has turned Gingette in once, Gingette loses her trust in Gingy and will perpetually turn Gingy in every day onward. The same happens vice versa.

- The two gingerbread people are rational creatures and would rather lose a bite tomorrow than today. However, they can choose a value X < 1 to denote how much they value a bite tomorrow compared to 1 bite today. For example, if they choose X = 1/3, they will consider a bite tomorrow as only 1/3 as bad/painful as a bite taken today.

The Question:

What is the minimum value of X for required for both Gingy and Gingette to perpetually choose to spare each other, leaving Farquaad hungry?